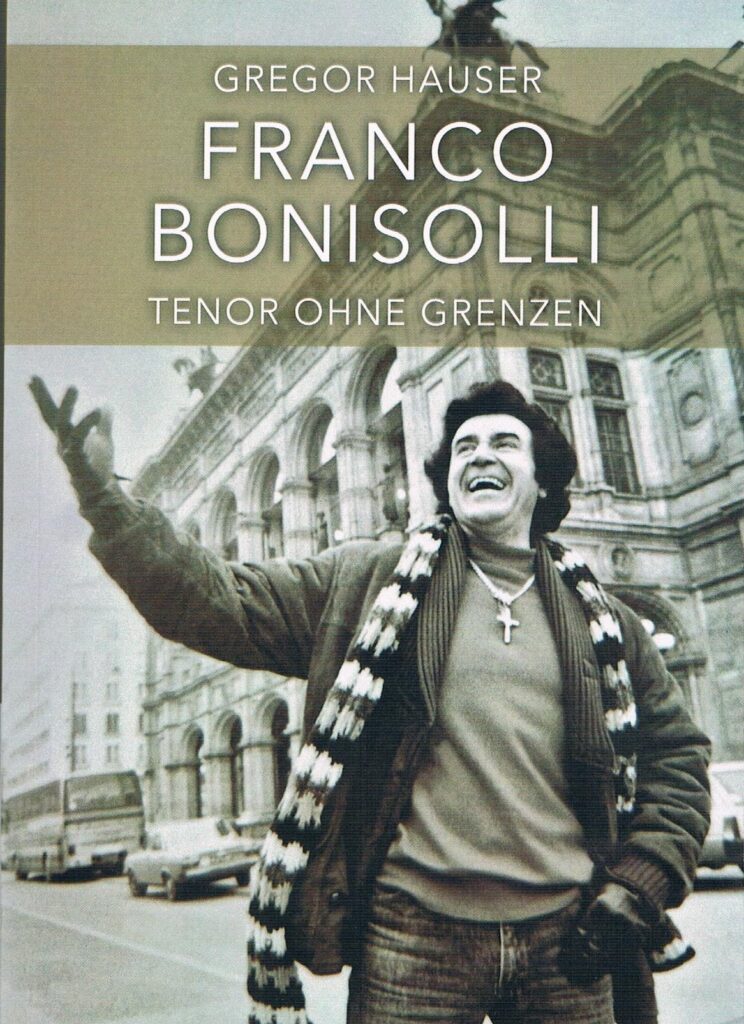

292 p.; Verlag Reinhard Marheinicke -Hamburg 2024.

The book is easily available on Amazon.

Mr. Hauser is a 47 year old Austrian tenor buff who already gave us “Magische Töne”, biographies of and interviews with post-war Austrian tenors; most of them well known in the German and Dutch speaking countries; less known in the Anglo-Saxon World. At the end of this Bonisolli-biography he honestly tells us he never spoke – and more important- saw or heard Bonisolli in the flesh. This makes a lot of difference as the author cannot tell us his own experiences and has to rely on reviews of performances and articles on Bonisolli’s sometimes crazy behaviour. He mentions many mails with the tenor’s family and some of his most ardent fans.

Nevertheless the author has done a thorough job though I regret there is not a separate full chronology or discography. All is in the book but into the text proper. We get the full story of the tenor’s poor background in the south of Tyrol; grabbed with France’s blessing by the Italians after the first world war though mainly German speaking. Though there is a German name in Bonisolli’s ancestry, the tenor is clearly from Italian stock. Bonisolli got almost no education and performed a lot of menial jobs in his youth, most of the time in a hotel. He therefore was mainly self-educated and was not only fluent in his own language but in English (due to his first wife) and French (he lived for a time in Monte Carlo) as well. Strangely enough he never learned German though Germany and Austria were the centres of his singing career. Still his German pronunciation in a few popular songs proves he picked up the right sounds. Vienna was the only place with its own fanatical fan-club “Amici di Franco Bonisolli”. Everybody who knew the tenor well emphasized he was not always keen of discussing singing and other tenors (though he was not shy to heap his wrath on competitors) but preferred conversations on philosophy and psychology.

Francesco (his real first name) Bonisolli was born in 1937. In his youth opera was still very popular on RAI radio and he was duly impressed as all his later tenor colleagues with Mario Lanza’s movies. His first contact with opera in the theatre was either in1955 of 1957 with Carmen at the Verona arena though he never told the name of the tenor he heard: either Franco Corelli, Mario Del Monaco, Carlos Guichandot or Vasco Campagnano. Probably Corelli who sang most of the performances and who became one of Bonisolli’s “bêtes noires” while he admired Del Monaco. He started his studies and in 1961 participated in an “international” singing contest. In reality Mr. Hauser writes the contest was purely Italian and it is one of the many corrections he has gathered to counter Bonisolli’s and his fans stories. Renato Bruson won in the baritone department while Bonisolli finished fourth in the tenor section. Two of his better competitors would have a decent career as comprimari. The big prize for 9 laureates was an opera performance and Bonisolli made his debut as Ruggero in La Rondine in Spoleto (there is a CD I never heard); though not in the well-known “Festival dei Due Mondi”. . According to the author the tenor was successful and not shy in sobbing his heart out even though Mr. Hauser writes there is no big tenor aria in the opera. In reality in those days the aria “Parigi è la citta dei desideri” was always cut. Bonisolli didn’t get an easy start. The period 1945 -1970 has deserved to be called “The new golden age of singing.” The year Bonisolli made his debut saw the emergence of Luciano Pavarotti. Nobody at the time could predict his astounding career and in those years he was not even the most promising one. Jaume Aragall, Renato Cioni, Bruno Prevedi, Veriano Lucchetti, Nicola Martinucci, Ugo Benelli, Gianfranco Cecchele, Giorgio Lamberti etc.etc. made their debut between 1960 and 1965. Therefore it was slow going for the tenor. He was not the most prolific student either but at one of his teachers places he met the aspiring American soprano Sally Taylor. They soon wed and she realized his was the greater talent and she went on to become his manager while she pushed him to study roles. Like all starters Bonisolli had to grab what he could. There is an interesting CD from 1962 with a live recording of Luigi Canepa’s Riccardo III, one of Verdi’s forgotten successors. We hear a young indistinct voice with an excellent top. Nothing in phrasing or colour strikes one as promising. Still a tenor who possesses the money notes and has “le physique du role” is never long without engagements. Bonisolli was welcomed at the Spoleto festival, met important people like Visconti, Schippers and Rescigno and soon got an engagement abroad. An assistant of Visconti – Franco Zeffirelli- took him to “De Munt” in Brussels for La Traviata. When soprano Franca Fabbri got indisposed Sally replaced her for one performance. Due to a visit of De Munt company in Berlin, Bonisolli sang five performances of Alfredo in the German capital. Another engagement was the one and a half aria in Rosenkavalier at the Rome Opera. More and more he filled his agenda with engagements at home and abroad. He was considered to be a light lyric tenor apt for operas like La Cambiale di Matrimonio. His looks even got him the part of Alfredo in a movie of Traviata for Anna Moffo, directed by her first husband Mario Lanfranchi. RAI too engaged him for a lot of radio performances though not for war horses. Works by Ricci, Scarlatti, Cimarosa, Pergolesi and Mozart (La Clemenza di Tito) were his fare. On scene he was considered “a worthy addition to the ranks” for world premières like Menotti’s The Saint of Bleecker Street in Spoleto or Nino Rota’s Aladino in Naples. With Bleecker Street he was part of a travelling company in The Netherlands where a critic wrote: “The voice is too light for the role of Michele”. Bread and butter operas he mostly sang in Brussels: Edgardo, Duca, Faust. According to Mr. Hauser De Munt was an internatiol opera house. In reality it was rather provincial and couldn’t pay high fees. Bonisolli was one of many provincial Italian tenors I heard in the theatre: Luciano Saldari, Ruggero Orofino, Renato Francesconi etc. Bonisolli’s rise therefore was far from sensational But every Italian tenor worth a bit of salt gets a chance at La Scala. For Bonisolli it came in 1969 with L’Assedio di Corinto (Sills, Horne). His role of Cleomene was deemed to be so unimportant that La Scala cast him on free days from the opera in concerts of Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette Symphony. In1970 he finally became a bit of a star. He sang the three last performances of Manon at La Scala (Pavarotti got the first ones) and as a reward got a premiere of Lucia with Sills.

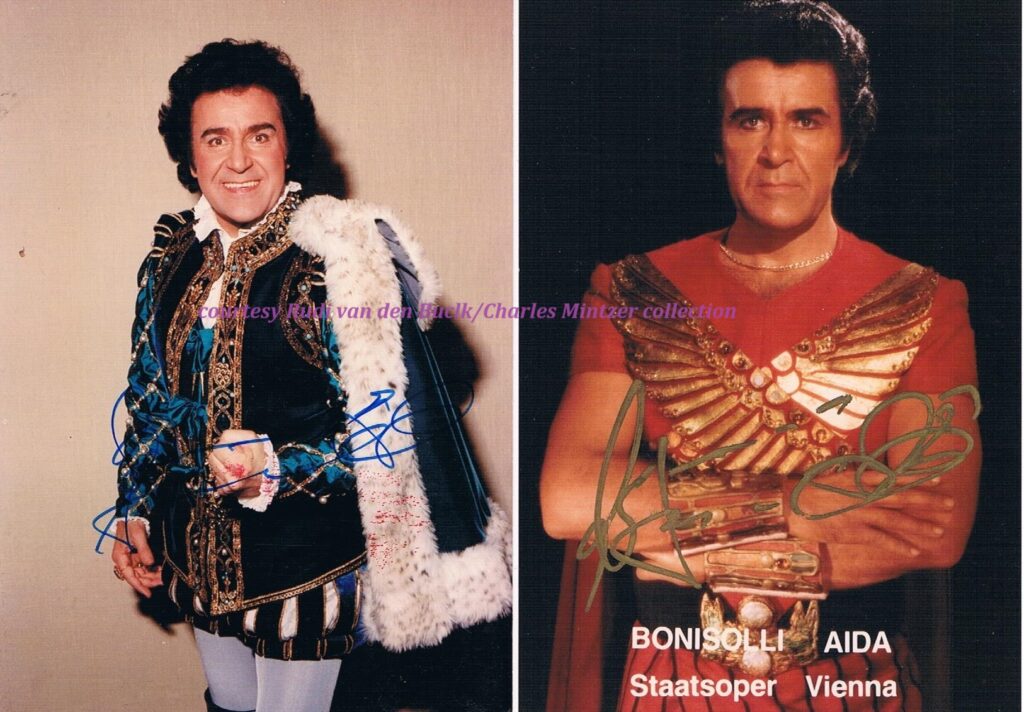

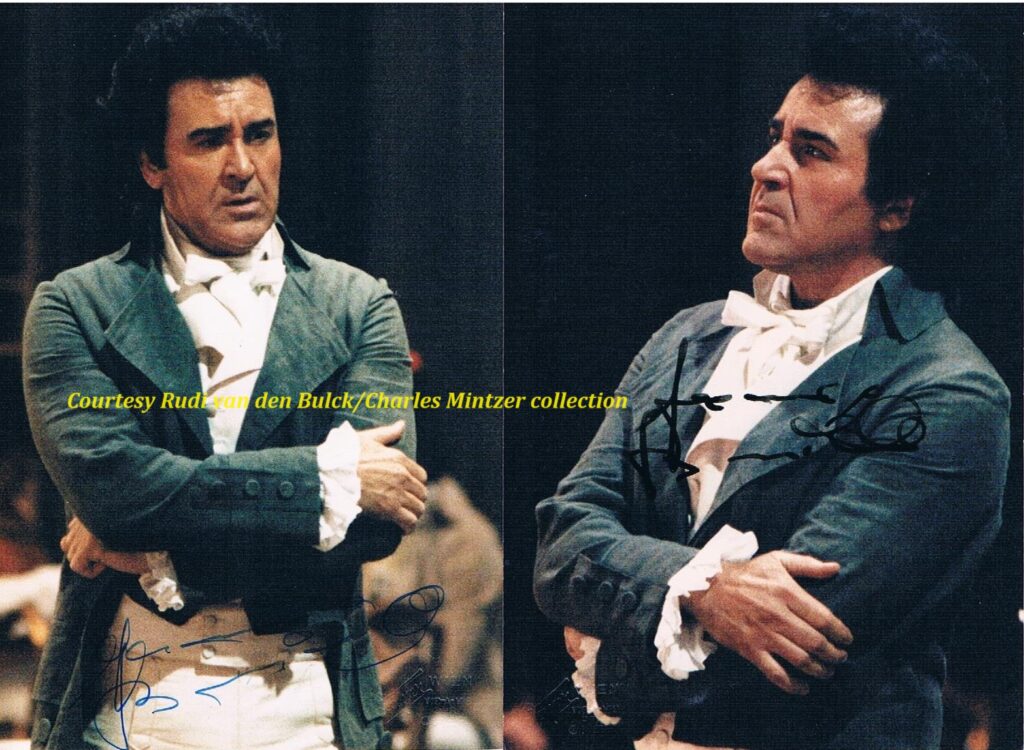

The seventies were his best years. Bonisolli made his debut at the Met in February 1971 with one performance of Il barbiere. He was clearly still considered to be a “leggiero”. He succeeded and came back at the beginning of next season with Elisire, Rigoletto, Faust and Traviata. We have no press reports from his performances but earth shattering they were not as he was not re-engaged for 14 years (A detail Mr. Hauser omits to tell us). In 1972 there is a last example of his galley years: the world premiere in Rome of an oratorio: Saint-Louis by Darius Milhaud. From now on it was smoother sailing with a storm now and then. As there is always a tenor shortage Bonisolli had no problems in securing well paid engagements; especially in Vienna and Hamburg. A real world star he never became. He got performances at the Paris Opera in Vespri after Domingo had left. He went to the rescue of Karajan in Salzburg when Pavarotti was ill. But he got plums as Tell with Muti as well. The voice changed. He sang more and more spinto roles and we have solo recordings as a testimony; not on the big labels as Decca, EMI or RCA but on modest ones as Acanta. The voice had changed. There was more sheen on it and it had gotten darker. Bonisolli’s glory was a magnificent top register and he had become a shameless top note hunter. Competitors too were not shy to interpolate a note not to be found in the score but they followed tradition (often approved by the composer) while this tenor surprised one with B’s and C’s in places where it simply distorted the musical line (e.g. Luisa Miller). Moreover it was not a world voice you recognize after a few seconds and there was no real sweetness or “morbidezza” in it. If the conductor held him in rein he could sing musically and even resort to piano as in a duet with Freni. Otherwise he sang legato while at the same time the sound barking. Love duets sounded like a quarrel. Phrasing was definitely not his strong point and there is no single phrase that leaps out. It’s not that Bonisolli constantly sobbed his heart out but a real sense of style was absent. Lack of elegance is often the main accusation.

Bonisolli recorded 13 complete operas though most were for cheaper German labels. A Tosca with Vishnevskaya on DG in 1976 failed as the soprano was past her best. He got a Trovatore with Karajan on EMI in 1977 and an I Masnadieri on Decca in 1982 with late Sutherland when Pavarotti couldn’t be bothered to learn the score. Probably his most enduring legacy is the fine recording of Leoncavallo’s La Bohème for Orfeo in 1981. By that time he was already known as Il Pazzo (the madman) as tenor and personal ego became more and more obvious. Mr. Hauser tells those stories in detail and they are worth reading. Only a dearth of good tenors can explain he still had a distinguished career. The best known of all those incidents is his quarrel with Karajan. The conductor who considered himself to be an important producer as well presided over a new Il Trovatore at the Easter Festival in Salzburg in 1977. The original Manrico (Aragall) cancelled at the last moment and Bonisolli saved the day. Karajan couldn’t do less than offer him the part in the Vienna Staatsoper during the reprisal in 1978. At the dress rehearsal with public his “Ah, si ben mio” was not well received. Karajan continued and Bonisolli refused to follow. The conductor ended the act with a mute Bonisolli on the scene. His lame explanation was that he was hungry. As a result he was dismissed and Domingo (the Staatsoper’s first choice) was flown in. The television broadcast, sold to a lot of European countries, was delayed. Domingo cracked horribly on the high B in “Di quella pira” (His last good note was a B flat and a few years earlier he had literally begged on his knees Met general manager Schuyler Chapin to cast him no longer in this opera). In other days such an incident could have meant the end of a career but at the end of the seventies and the beginning of the eighties a tenor who could hit the notes was never without a job. Next year Bonisolli finally got his chance in the Verona arena as the well of excellent Italian and non-Italian tenors had dried up. This was my last season at the arena. I was used to Domingo on Friday, Bergonzi on Saturday and Corelli on Sunday in 1970. The stars in 1979 were Bonisolli, Lucchetti, Dvorsky and the best of them: Cecchele. Bonisolli made his debut with Turandot and in the book a fan swoons over his performance. I mostly remember the voice was unexpectedly small (the founding editor has the same experience with other performances elsewhere); very much so compared with Domingo in the same role at his debut in Verona and in Italy in 1969. During the eighties Bonisolli’s career went slowly downhill though he got an engagement for a few performances at the Met. “He was a joke” wrote a reviewer. At the same time -and antics and all- he became even more popular in Vienna where his “Amici di Franco Bonisolli” celebrated him as if he was the second coming of Caruso. He even became a “Kammersänger” and scored hysterical successes every year on the 6th of January with a special concert for the fans. We have a Cd on Myto from 1986 and the difference with his best years is clear. The dark hue of the voice is less and the sound is more white. There is a beat but the redeeming feature are the still imposing top notes. In 1990 he gave his final performances and seemingly disappeared until he unexpectedly returned 9 years later with concerts and even a few operatic performances and several scandals as well (for details, buy the book). He didn’t’ t leave with honours but ended his career at the Taormina Festival in Sicily in 2002 after one last spectacle of boorish and vulgar behaviour and a violent reaction from the public.

Mr. Hauser gives us a full portrait too of the tenor and his hobbies: cooking, cycling and women; especially women with a weakness for chorus members. He made his wife so unhappy she tried to commit suicide. Sally died of heart failure and he soon found a new spouse. A brain tumor put an end to his days on the 30th of October 2003. Even in his death he had bad luck as Franco Corelli had died the day before and got all the notices in the press while Bonisolli was relegated to a few lines for “another singer who left us”. Bonisolli called his far more famous colleague Franco Orelli because the tenor from Ancona often transposed high notes (and sounded more impressive with his B’s than Bonisolli with his C’s). All in all, Mr. Hauser has given us an interesting portrait of Franco Bonisolli, many warts included.

Jan Neckers