(Part one – 1910-1950)

A visit at Olivero’s

“Era un nume” Magda Olivero told me. “He was a God” and that god was Enrico Caruso; the one great tenor whom she never sang with as she was too young. But she remembered well the horrified exclamations of her father when he read in his newspaper Caruso had died. I met her for a long talk in her magnificent apartment in the Italian seaside resort Rapallo in 1987. The Dutch-speaking public broadcasting organisations had decided on a co-production of an Italian language course. A documentary on Italian culture would be produced as well and as the Flemish producer I proposed one on the breed that for almost hundred years was the symbol of Italy in Flanders and The Netherlands: “The Italian tenor”. I baptised the programme “Sei fuggita e non torni più” (from the song “Rondine al nido”) as the breed was almost extinguished at the time and has nowadays disappeared. I’d found rare footage (rare in these pre-Youtube-days) and started working the phone. First I tried Franco Corelli as he was the only top tenor who during his career had his number at Via Crivelli 12 in Milan (photo on his first Neapolitan Song LP) in the public directory. No answer. Next I tried Carlo Bergonzi. During the shooting he would be somewhere in the south for Zeffirelli’s movie on young Toscanini. Time for “the only great tenor to come out of Italy for a whole generation” (courtesy of Decca’s publicity department). I have no idea anymore how I got Pavarotti’s phone number but he answered himself and was interested in an interview. However I had to clear it with a certain Breslin. I duly phoned the guy and promptly got the question : “What do you pay”? It was not our habit to pay for a journalistic chat but the Dutch had informed me I could offer 500 $. “Forget it” Breslin barked and threw his phone down. Well, I still had Di Stefano’s number. I phoned him and a well-known voice told me the tenor was not at home and what did I want? I explained and added we would eventually pay the tenor for an interview. “Son io Di Stefano” the rogue said. I mentioned my 500 $ and his reply was: “Poco, poco” but he agreed. The next step was easier. I wanted a soprano as well and an ardent Antwerp fan of Renata Tebaldi and Magda Olivero helped me out. She knew both ladies very well (Tebaldi later said to me that if somewhere on the world someone had recorded a note of her singing, that Antwerp fan had a copy). The fan warned me. Tebaldi would never pick up her phone as that was the task of Tina. I would have to show patience as I wouldn’t immediately get an appointment. “Domani” Tina told me and afterwards it became “dopodomani” and so on till I finally got to see the lady in Rimini. It was old-fashioned prima donna behaviour probably fuelled by a poor background presuming a world star cannot comply too fast. The contrast with Olivero was marked. That lady derived from a family of aristocrats and didn’t think it necessary to hide social insecurities behind prima donna behaviour. I phoned her and yes there was a lady companion too but within a minute Olivero answered herself, listened, took her agenda and we had an appointment. Thus I met her at her apartment. I brought flowers with me which she graciously accepted. We took a seat and she made the mistake of addressing me in French as in her youth Belgium was still thought of as a French speaking country (some backward Americans still think so). In those times the 60 % Dutch speakers of Belgium were barely represented in diplomacy, aristocracy and finance. French was the first foreign language she learned in her youth but her command had become very rusty and she was clearly relieved when I told her I spoke Italian. She offered me a drink and gave me a lesson in old world etiquette. I had noticed a slight trembling in her hand and I wanted to pour out my cup of tea. She decidedly took my hand and said: “it is my honour to serve you”.

(video clip unearthed by Mr Neckers for his TV programme and then of course copied all over the web)

YOUTH

Maria Maddalena Olivero is born on the 25th of March 1910 in Saluzzo; 50 kilometres to the south of Torino (Turin); capital of Piemonte and the kingdom which 50 years earlier succeeded in uniting Italy. Magda is the younger sister of Teresa Olivero. Their father is born in the royal palace of Turin as her grandfather is an important courtier. Father Federico rises in the judicial hierarchy and mother Adele shows a lot of talent for drawing and painting. When Magda is five her father is appointed a judge in Turin. Federico is an avid opera lover and regularly visits the Regio (where Manon Lescaut and La Bohème get their world premieres) and the Carignano. . He himself has a beautiful tenor voice and is not shy to prove it. His youngest daughter inherits his love of music and as a child likes to sing during visits of family and friends. Her favourite song is “Torna a Surriento”. Olivero grows up in surroundings of privilege and she is not typical of Italian women of her generation. She measures 1 metre 67; almost 10 centimetres taller than most Italian women at the time and she is a stunning beautiful blonde. She has two hobbies: cooking and studying. Olivero is known to be charming, courteous and at the same time all her life a bit aloof. She doesn’t share girlie secrets with friends. Her great love is music. Father Olivero hires well known composer Franco Ghedini to teach his daughter piano, harmony and even counter point. And she takes singing lessons. At first father and mother stimulate her. After all Olivero should marry a high civil servant, an officer or a rich bourgeois and is to have her own salon where she can entertain her guests with piano pieces and a few “romanze di salotto”. Olivero devotes more and more time to serious singing lessons and slowly it dawns upon the family (and worries them) she might have a career. That is not acceptable. Italian singers are bred in families of skilled blue collar (Caruso’s father was a foreman) or white collar workers, craftsmen, shopkeepers etc. Singers from uneducated proletarians or farm workers are rare and so are singers deriving from upper classes (Mario Del Monaco too is an exception). The Olivero’s appeal to the well-known conductor Ugo Tansini. Olivero desperately wants to study at the Instituto di canto di Torino, recently founded by Eiar (later RAI). Tansini has to stop Olivero’s career. Her audition is a catastrophe. Tansini notes: “She has no voice, no musicality and no personality.” “All’s well that ends well” father Olivero thinks. He underestimates his daughter’s stubbornness. Madamigella Olivero doesn’t give up, has important relations and demands a second audition. Tansini complies, remains negative but there is another teacher who hears a sparkle of talent. “Lose your time and teach her” is Tansini’s reaction (later on he conducts her first recordings).

DEBUT

Luigi Gerussi teaches Olivero breath support. She has to learn to use every muscle of belly, back and diaphragm. For months she doesn’t succeed coordinating muscles and brains and she often cries from rage and despair but she is not a quitter and one day there it is. And finally she can start a career. At the end of 1932 she gets to sing a few measures (once more, relations) in an oratorio at Eiar. One year later she gets small roles in Maria Egiziaca (Respighi- with Tagliabue and Pacetti) and La Legenda di Sakuntala (Alfano) at Eiar. She gets a few concerts too on radio and sings arias which will accompany her during her whole career: Manon, Adriana, Fritz, Mefisto, Manon Lescaut. She finally makes a debut in an opera house: Lauretta in Gianni Schicchi (with Montesanto, Baccaloni and conducted by Capuana) in the small Teatro Vittorio Emmanuele (now auditorium Toscanini). All this takes place in Turin under control of “la famiglia”. But when La Scala offers her a few small roles plus an education in all matters operatically father Olivero initially refuses though his daughter is 24. Finally he relents as he knows his daughter will not become the usual “donna di teatro” who falls for the first tenor charmer. On the contrary, she doesn’t mince her words when speaking her mind on colleagues without her culture and manners (read on for examples). In interviews she often shows disdain for powerful conductors or singers. It probably doesn’t help her in her career but all her life she is financially independent.

EARLY CAREER

At the end of 1933 she makes her debut at La Scala in the small role of Anna in Nabucco (Cigna, Galeffi, Pasero, Gui). Next comes Ines in La Favorite (Pertile, Stignani); followed by once more an engagements at Eiar Torino (Nanetta in Falstaff with Caniglia). Even a lady with relations in well-off classes has to follow the difficult road. For eight months she auditions without getting a role and she uses the time for further study. Then she gets a few roles with Carro di Tespi (Thespis’s wagon). From 1930 on the fascist government (Mussolini considers himself all his life to be a leftist) decides on a company which visits small cities with a theatre without a real opera stagione. Tickets are very low priced to get less wealthy people in the house. Singers in Carro are well paid by the fascist government. With Carro Olivero sings the first of her three Verdi roles: Gilda; the two others being Violetta and Nanetta. She immediately realizes her rich vibrato and clear voice is not suited for the Leonores, Aidas and Amelias. Puccini is more apt for her voice and in 1936 she adds Mimi and Butterfly to her roles. At Eiar she sings Manon and I Quatro Rusteghi. 1937is a special year. For the first time she is fully booked. Fascism likes to categorize people. All singers are put in their own category and following a bureaucratic system paid accordingly (Gigli and conductor Mascagni are the monkeys on top of the rock). Italy abounds with soprane lirico (Olivero’s category). There are 250 competitors and all means – nice and dirty, mostly dirty- are used to get a role. Young hopefuls during Olivero’s early years are Iris Adami-Corradetti, Franca Somigli, Pia Tassinari (still a soprano), Sara Scuderi, Augusta Oltrabella, Stella Roman, Lidia Cremona, Ines Alfani-Tellini and Olivero’s nemesis Licia Albanese. They passionately hate each other and people who knew them both told me that with old age their feelings didn’t change. Albanese leaves for the US before the war but Olivero stays in Italy.

Italian singers have to earn their fees in a fascist country and singers in the lower ranks are beggars and cannot be choosers whatever they think of politics. Olivero often performs in fascist benefit concerts. She sings Mimi at the Sforzesco castle in Milan for 30.000 fascists. Typical Olivero is the fact she has no qualms in having a thanks letter publicized by the fascist organisation in her authorized Italian biography (1984). Contrary to their German counterparts Italian singers often don’t want to rewrite their own role or the history of their country (In an interview Renata Tebaldi tells her voice is discovered at school singing “Giovinezza”, “Ballila” and other fascist hymns). During these years Olivero mostly performs in provincial theatres but at last she gets a contract for the Rome opera. Conductor Tullio Serafin promises her she may sing Philine in Mignon as she still has an F. In exchange he asks for payment “in natura”. We know that small old grey man from the Callas-Di Stefano and the Tebaldi-Bergonzi recordings but a younger Serafin is not ashamed to ask for sexual favours. Olivero refuses resolutely and as a revenge he casts her as Elsa in Lohengrin. At Eiar in Rome she sings the role of Katiusha in Alfano’s Risurezzione (with Pau Civil and Tito Gobbi). Lucky for us she repeats the role 34 years later for RAI and we have a recording in fine sound of Alfano’s first and best opera. Alfano is the head of Torino Conservatory and he recommends her to Umberto Giordano whose Mese Mariano she performs (The Alfano biography by Conrad Dryden has a foreword by Magda Olivero). 1937 too is Olivero’s….Monteverdi year with a lot of Incorazione di Poppea and Il combattimento di Tancredi next to Butterfly, Manon and Bohème and even Don Giovanni.

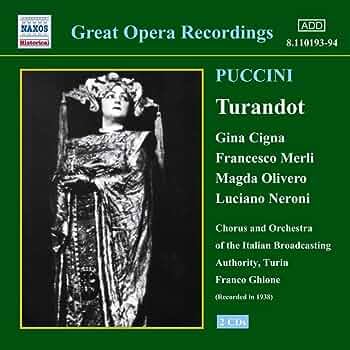

1938 is her first year as a real prima donna. She finally receives her crown in Prato when for the first time she has to encore an aria: “Tu che di gel”. One often forgets Olivero is sixteen when Turandot is premiered. For a whole generation afterwards Italy awaits a successor for Puccini and everywhere modern operas are performed in the hope that a magnificent tradition hasn’t come to an end. Managers know Olivero’s deep knowledge of music, her ability to memorize a new score in short time and thus are ready to offer her a lot of work. In Trieste and Genua she sings in La caverna di Salamanca; an opera by Felice Lattuada. This is followed by an offer she has long been waiting for: a star part at La Scala. Giordano asks her to sing in a new production of his Marcella and she is partnered by Tito Schipa and Giovanni Manacchini (who ends his life at the Verdi Casa di riposi). A small role is sung by Giulietta Simionato. During rehearsals Giordano asks her to act more intensely but Olivero knows the tenor’s reputation and his tendency to use his hands during the love duet. After Marcella it’s back to a modern opera: Pick-Mangigialla’s Notturno Romantica at her debut in Palermo. At Caracalla she first sings in a giant open air performance in Turandot. Kalaf is the popular Galliano Masini and Olivero makes short shrift of him. “On scene he was a real prince” she told me “off scene he was a brainless and vulgar pig”. Then once again modern works are her part: L’ultimo Lord by Alfano for Eiar and La Monacella della fontana by Giuseppe Mulé in Bologna. The crowning affair of the year is her Liu in the first complete recording of Turandot with Merli and Cigna; still a reference recording. For the first time we hear a voice that in 30 years will not change much though on this recording the sound is less personal than we later are used to. One immediately notes the strong vibrato; some will even call it a tremolo and especially in Anglo-Saxon countries this sound is less welcome. Next one is stricken by the intensity of Olivero’s phrasing and her abundant use of messa di voce. The voice is clear and fresh, no hints of a darker sound, and has warmth. It is not a voluminous one but Olivero projects so well nobody in the theatre or even an open air arena complains. Olivero starts her career in the heydays of verismo singing and there is always a tear or a sob in the sound though not the madness of Lina Bruna Rasa. Olivero has no inkling that this first successful complete recording of an opera will be her last till 31 years later Tebaldi cancels Fedora. Cetra (recording label of Eiar, later RAI) asks her to record some arias: Adriana and Mefistofele and the magnificent Amico Fritz duo (with young Tagliavini) in 1939, Adriana, Traviata, Manon Lescaut, Tosca, Bohème (2), Louise, Gianni Schicchi in 1940. This is not an exceptional honour. All good sopranos are signed up by recording labels for at least a few 78’s and vocal buffs sigh when they reminisce on “Cetra-sopranos” and other shellack-ladies.

WAR

At the moment Olivero’s career seems to take off it almost comes to an early end. With Italy’s conquest of Ethiopia (called Abessinia at the time) in 1935 troubles start internationally (Tophit of 1936 is “Facetta nera, bel Abessinia” as fascism is still not racist.) Next year Mussolini supports with thousands of soldiers a putsch by arch reactionary Franco (not a fascist) in Spain. Italian singers are often identified with the regime and world stars as Gigli, Schipa and Lauri Volpi are ardent supporters but remain welcome everywhere while lesser luminaries often are not. Fascist aggression goes crescendo when Italy attacks Albania on Good Friday 1939 and conquers it. Younger singers who still have to build a world reputation therefore often stay in Italy. After all there are 260 opera stagione in the country. Oliver widens her repertory in 1940 and 1941; mostly with modern works: L’Aiglon, Cyrano de Bergerac (Alfano is pleased), Cleopatra (by conductor Armando La Rosa Parodi’s) and het debut in Turin’s Regio. Nevertheless this is no longer 1900 when audiences are so sophisticated (or think they are) they laugh at operas from Verdi or Donizetti, consider them to be old fashioned with melodies worn out by street organs. By 1940 it gradually dawns upon Italian opera visitors that melody is no longer the bedrock of opera. Opera too is not longer everybody’s favourite music as democracy and modern technology produce mass markets for hits which show respect for an easy charming melody. “Il tenore del popolo” Beniamino Gigli has seven pages in pre-war Voce del Padrone record catalogue but pop singer Carlo Buti (magnificent timbre) has twenty-three. Opera managements gradually programme older traditional works by still living composers. Olivero sings a lot of performances of L’Amico Fritz, Francesca da Rimini, Giulietta e Romeo (Zandonai) and is one of the soprano’s after Dalla Rizza and Melis who restore a forgotten opera: Adriana Lecouvreur. She first sings the role in 1939 during a radio performance in Rome with Gigli (some parts have survived). One year later she sings it on scene in that same city and with the same tenor. It is a well-known story she relished telling (I too got it with all details). In 1940 Gigli has been back in Italy for eight years after his New York career practically ended in a terrible clash with general manager Gatti-Casazza. From now on he performs two or three roles each year in the Italian capital and gives a lot of concerts as well in Rome. Of course Romans like him but he is no longer a fresh young singer bursting upon the scene. He has sung Maurizio in Adriana in Rome in 1936 (with Pederzini and Cristoforeanu) and therefore attention is fixed upon young Olivero at the performances in March 1940. The soprano gets bigger applause than the tenor and Gigli is angry, lingers in his dressing room and threatens to quit and not sing the second performance if the same soprano remains in the cast. Management warns Olivero and she has a solution. Before the performance an admirer sent her orchids. She picks one up and knocks politely at Gigli’s dressing room and says: ”Commendatore, allow poor little Adriana to offer a flower to the great Maurizio”. She told me Gigli didn’t smile at first but then he relented and accepted the flower. She added that she did her best during the rest of the performance to stay as most as possible at one of the sides of the scene and let the centre to the tenor. She finally made an auspicious remark. She had sung with all great tenors from Pertile to Pavarotti. Most took their difficult job seriously; after all they sing in an unnatural tessitura for a man. According to Olivero Beniamino Gigli was in her experience the only tenor who really enjoyed his profession. Olivero said to me Gigli had “la gioia di cantare” in his eyes.

Eleven weeks after Olivero’s clash with Gigli Mussolini decides he wants part of the spoils of Hitler’s Blitzkrieg in Western Europe and he declares war on the British and French empires though Italy is ill prepared. For a while life goes on in Italy’s theatres. In April 1941 Olivero concertizes in Predappio, a small city in Emilia Romagna but Mussolini’s birth place (and still a place of pilgrimage; supported by the leftish city council as tourists bring in money). Afterwards she is invited to Berlin Charlottenburg where she sings Giulietta e Romeo with Alessandro Ziliani, Francesco Albanese and Loretta Di Lelio. For the first time she has to run for shelter as British planes bomb the city. War comes closer and she has an extra reason to empty her agenda. At the end of May she sings Adriana in Ravenna and her career is over. She is engaged to a rich industrialist Aldo Busch and she intends to follow her mother’s footsteps. Marry, take care of the household (with a lot of servants), raise children and look after her husband. Finito il teatro. She marries in a small church in the vicinity of Piacenza on the 19th of June. Two days later Hitler starts the invasion of the Soviet Union.

LIFE OUTSIDE THE THEATRE

Signora Busch initially lives in comfort in Turin. But the city is the heart of industrial Italy and in 1940 British planes already bomb the Fiat factories. The situation worsens considerably in 1943 after the allies invade and conquer Sicily with its many airfields . Italy capitulates and shortly afterwards declares war on Germany. The country is accepted as a co-belligerent but not as an ally and Americans and British mercilessly bomb the north of Italy where Mussolini governs a puppet state under German occupation. Turin suffers and the city is fully darkened at night. During day fascist militias rule in the streets; at night partisans roam the city. At the same time Olivero suffers personal tragedy. She is pregnant with a boy and loses her child in a miscarriage. A second pregnancy ends badly too. She runs from doctor to doctor, listens obedient to councils by anybody but nothing helps. These are desperate years of despair until the Busch family realizes there will be no children. Friends and relations advise Olivero to sing to relieve her pain. She may not throw away God’s gift to her but this is not much of a consolation. Singing in the theatre is definitely not an option for a lady. Moreover far too dangerous to travel as allied planes shoot at every train. During the first months of 1945 civil war rages in Italian cities. At the liberation at the end of April 1945 Olivero meets with no difficulties as she has not sung in four years and did not perform in Mussolini’s German controlled Republica Sociale.

A NEW START?

War is over and Olivero takes up her former haute bourgeoisie life with a lot of social contacts. For domestic chores she has servants. There are no children and she gets bored. From time to time she meets singers and conductors who remind her of her opera career which is no longer possible for Mrs. Busch. Performing in a theatre is still out of the question though singing for the joy of making music remains possible. And luckily for Olivero there is the old catholic tradition of charity. In April 1946 she gives a concert in a church in Reggio Emilia; “sacred” arias of course. A few months later she concertizes in an orphanage and for the first time she sings in public her old operatic successes. That’s enough for now with only one concert each year in 1947 and 1948. By 1949 change is in the air. Olivero concertizes three times for charity in a Reggio church and sings two concerts with operatic stuff in a “circolo sociale” in Saluzzo, her birth-place. Rumours start in Italy’s operatic circles when in 1950 she gives two concerts in theatres. Olivero receives a letter and later a visit of the head of Sonzogno who asks her to appear once more in Adriana Lecouvreur (published by his music firm). He is accompanied by her old enemy Tullio Serafin. The conductor however is the ambassador of Francesco Cilea; old an ill and he has the same request. In August she receives a personal letter from the composer who expresses his wish to listen to her just once in his opera. She visits him and he accompanies her at the piano in “Io son l’umile ancella” and “Poveri Fiori”. At that moment she has already taken the decision to resume her career and Aldo Busch knows he can trust his 40 year old wife in the hotbed of Italian opera theatres. Italy’s best known operatic critic Rodolfo Celetti welcomes her return. He writes : “ The voice is rather small but very intense, there is more than a hint of a tremolo but the sound has squillo. Olivero enlarges or reduces her voice to barely a whisper whenever she feels she’s in the mood. It’s almost a miracle and there is no soprano at the moment who can compete with her in this way. Her diction and phrasing are exemplary and she never forces her voice and her top notes are pure. Moreover we remember her as a fine actress. “

Olivero now seriously focusses herself on a new start. She has not sung professionally in ten years and has to restudy. But her vocal cords too have had a rest and physically she is strong as a horse (her own words to me). She has become a vegetarian and practices yoga. Contrary to legend she doesn’t make her debut with Adriana but starts her second career with La Bohème.

Jan Neckers